“Modern Criminal Evidence”

Walter Owen Book Prize (First Place) – 2023

Canadian Foundation For Legal Research

08 April 2024

IN MEMORIAM

LEWIS, Grace Knight

Serenely, Grace Knight LEWIS (nee French) passed,

age: 96 years, at St. John’s, on 13 October 2024.

Predeceased by parents Stanley and Frances (nee

Taylor) French; by her love of 56 years, her husband, Honorable P. Derek Lewis Q.C. (19 January 2017, 92 years) and their

daughter Baby Lewis (who died at birth); by sisters Elizabeth (Hon. Charles

Granger) and Louise (Bud Osmond); by only brother Edward, and by ‘Sugar

Loaf’.

Left mourning: her sister Josephine French May

(Hamilton) of Colborne, Ontario; sister�in-law Sylvia French (spouse of

Edward); nieces Kathryn (‘Kathy’), Cynthia (‘Cindy’), Annette, Marlene,

Lisa, Susan, Julia, Debbie, Olivia (‘Pip’), Elizabeth, Sally, and Brenda;

nephews Philip, Lorne, George, Howard, Douglas (‘Doug’), Christopher, and A.

Stephen; and numerous grand nieces and grand nephews.

Also left mourning: cherished adult lifelong

friends Joan Blackmore, R.N. and Stella (Blackmore) Mifflin, as well as

David C. Day and his wife Bernice Blackwood; Grace’s personal assistant and

loyal friend (of 27 years) Kelly A. (Mahoney) Hall, and her husband Tom and

their daughter Kaitlyn; her physicians Dr. Michael J. Kennedy and since

2018. Dr. Mercedes D. Penton; her physiotherapist Brad Hopkins; her property

manager, Dominic McCarthy; companion carers from CareGivers NL, especially

Suborna Rahman, and management and eighth floor care providers at Tiffany

Village, St. John’s where Grace resided since 2018.

Grace was born at Moreton’s Harbour, New World

Island, Notre Dame Bay, Newfoundland, 25 February 1928 (into the French

family; which first settled in Newfoundland in or shortly before 1634, at

what is now Bay Roberts, and since about 1832 has resided in Moreton’s

Harbour).

Among her most treasured possessions, a painting

recalls, and an inscribed bible recognizes, her vital role in saving from

fire the 400-seat Moreton’s Harbour United Church.

The 1997 painting of the church was created for

Grace by Latvian artist Wally Brants (months before his passing in 1998).

The inscribed bible was, for many years, thought

by Grace to be mislaid. In November 2022, the result of a search she

requested, the bible was discovered by her personal assistant, Ms. Hall. The

bible (including silk bookmark resting at 2 Kings, Chapter 22; some of her

Sunday School notes; her baptismal certificate, and 4-leaf clovers marking

Psalms 46 to 50) was wedged into the back of a bedroom dresser drawer at her

former residence, century-old 6 Circular Road, St. John’s.

On a January afternoon in 1937, Grace (then 8 years

old) was the only sibling from her family to walk through a Moreton’s

Harbour blizzard to the United Church. On arrival outside, she realized from

absence of footprints that she was to be the only student from the Harbour

to attend the United Church Sunday School class that day. When she opened

and started entering through the door to the sanctuary at the back of

the Church, near the classroom, she was decisively denied entry by a wall of

heat, fumes and smoke. She was forced back into the storm.

As she recalled, in November 2022: “I was

temporarily blinded. When I collected myself, the church back door was still

open. I had to close that door. Otherwise, the wind would fan the fire

inside and the church wouldn’t stand a chance. The stove inside the back

door had overheated. There was fire on the floor. Some seating finished in a

glossy varnish had begun smoking. I went forward with all my might and,

wearing my snow mittens, I eventually forced the door shut. Then, I

struggled through gales and snow banks to the next garden. That’s where the

Sunday School superintendent Hedley Knight lived. I reported the fire. And

then, as if such was necessary”, doubted Grace, “he called to his son, to

investigate. When the son confirmed the fire, the superintendent rang the

church bell in a tower attached to the front of the church. He rang rapidly.

This was a signal of danger. From near and far, every able-bodied occupant

of the town, whatever they believed, responded on foot or by sleigh to the

United Church, and joined us to extinguish the fire.”

In 1938 she was recognized, with a bible, for what

minister Rev. R.C. Hopkins called her “bravery”. A church history, published

in 1996, recorded that the bible, presented by Church Recording Secretary

Hedley Brett, acknowledged Grace for “her quick action in saving the church

from total destruction.” The bible was inscribed: “presented for services

rendered in connection with church fire… .”

Grace was, in 1944, graduated from high school at

Moreton’s Harbour United. She chose teaching as her life’s vocation. To

prepare, she spent summer 1944 at Memorial University College (MUC), St.

John’s, undertaking the Summer School Teachers’ Training Course. On 11 July

1944, Dr. James McGrath certified her “physically fitted to undertake duties

as a School Teacher”. Such she proved to be, though much more “physically

fitted” than Dr. McGrath could have foreseen.

She commenced teaching in September 1944. As

always, she taught kindergarten and grade one pupils.

Grace’s first teaching assignment — at age 16 years

— took her (so she understood) to the United Church school in a Green Bay

village. That assignment abruptly ended in less than four months. Most

pupils, and their parents and other adults, in the village proved to be

fervent disciples of a charismatic Christian faith, to which they had lately

converted from United Church doctrine. Daily, on school days, many of

them—both pupils and their parents—pelted Grace with stones and later, snow

balls because she refused to adhere to their faith. They hailed her on

village streets as “doing the devil’s work” because she was known to play

‘auction 45s’ and other card games with her only two village friends; a

lumber merchant and his wife. A United Church education administrator

re-assigned her. In much more civilized and congenial Botwood, she was

expected to complete her first year of teaching.

But during Botwood’s 1945 winter, she did not. Her

premier teaching year was, within weeks, again interrupted. She was confined

to her boarding house. Three or four times daily, she was medically examined

(although she never regarded her health as impaired, and she never warranted

diagnosis). Botwood had experienced a diphtheria epidemic. One of her

students died from the disease. If school resumed that year, she said

in November 2022, the duration was brief. She subsequently taught for

several full school years, beginning September 1945, at Botwood (preceded by

more summers of MUC school teacher’s training). Later, she taught in Bay

Roberts at Amalgamated (1950-1951), then in St. John’s at Prince of Wales

College, LeMarchant Road (while the College included an elementary school).

Not until 1947—at age 19 years—had she formally qualified, from MUC summer

studies, to be a Kindergarten and First to Third Grade teacher.

As a teacher, she routinely was involved in

distributing cod liver oil to her pupils to be brought home for daily

consumption by their families. She appeared, as a teacher, in a media

campaign promoting that dietary supplement.

She forfeited seniority when she took leave from

her teaching position in St. John’s to care for her ill mother in Moreton’s

Harbour. The United Church minister’s wife there taught her secretarial and

office management skills. Those skills she put to use when, on eventually

returning to St. John’s, she joined her sister Josephine at a finance

company.

Although she never again taught school, she

undertook education which, by November 1992, qualified her as proficient in

written and oral French language.

After marriage, 21 October 1961, she assisted her

husband for 54 of his 68 years practicing law in St. John’s, and in his

public life as a member of the Senate of Canada (1978 to 1999). She was

introduced to him at Old Colony Club, Portugal Cove Road, St. John’s during

a dinner which each had attended, unaccompanied. That night she told Derek,

“learn to dance, or you won’t advance,"

GOWER STREET UNITED CHURCH, ST. JOHN’S, 21

OCTOBER 1961

Their preferred recreations were swimming, aqua

sailing, snow shoeing, brush hogging, and ice boating. On their 12-by-8-foot

wooden iceboat, Grace and spouse manipulated its single canvas sail in brisk

winds to catapult themselves over Quidi Vidi Lake. Most of their 27 acres of

largely-wooded cottage property at King’s Road, Hogan’s Pond, St. Philips,

was by them—with assistance of Grace’s brother Edward French – neatly

cleared of brush using only hand tools. They were ‘regulars’ at St. John’s

Arts and Culture Centre performances.

She cherished memories of occasions in England, at

each of Buckingham Palace and Windsor Castle, and in Canada, when she and

her spouse met, and chattered with, Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip.

Much more voluble, she recounted, were members of

Canada’s political community; hundreds of whom she encountered during her

husband’s senatorial remit.

Remembering Grace K. Lewis celebrates a life that

was ever unassuming, forgiving, patient, thoughtful, dedicated, comforting,

and sensitive; always seasoned with gentle humor.

Cremation has occurred (Carnell’s). At Grace’s

request, neither a wake nor a public service will be held. A private family

service, followed by inurnment, will be conducted on a date to be announced,

at Anglican Cemetery, Forest Road, St. John’s, to reunite Grace with husband

Derek and their daughter, Baby Lewis.

24 SUSSEX DRIVE, OTTAWA, AUTUMN 1971

Grace K. Lewis (second left in foreground)

and spouse Honorable P. Derek Lewis, Q.C., meeting Prime Minister Pierre

Elliott Trudeau, his then spouse Margaret Trudeau and, en ventre sa mere,

future Prime Minister Justin Pierre James Trudeau (from copyrighted

collection of Estates of Honorable P. Derek Lewis, Q.C. and Grace K. Lewis).

(THIS ‘IN MEMORIAM’ OF GRACE KNIGHT LEWIS (NEE

FRENCH) IS CONTRIBUTED BY HER LEGAL COUNSEL AND FRIEND SINCE 1968, DAVID C.

DAY, K.C., OF LEWIS, DAY LAW FIRM, ST. JOHN’S.)

|

IN MEMORIAM:

THE CANADIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR LAW AND THE FAMILY,

1987—2018

John-Paul E. Boyd, K.C., Calgary

(2019) 32:1 Can J Fam L 221

(When this

Calgary-based international research institute—known by the acronym ‘CRILF’—

was dissolved

by its directors, the core staff were barrister John-Paul E. Boyd, K.C.,

Executive Director;

Joanne J.

Paetsch, Research Director, and Lorne D. Bertrand, Research Associate.

The senior

director at dissolution was David C. Day, K.C.)

A Chronicle of the ‘First Five Hundred’

in Combat and Court

David C. Day, Q.C.

[An abridgement of what follows was originally published by Downhome

magazine, in November 2016,

under the editorial supervision of Janice Stuckless, the magazine’s editor.]

They have always been—and eternally will be—‘The

First Five Hundred’.

Who were the First 500?

In fact, they numbered 22 officers and 521 mostly unmarried volunteers; 543

military men, all told. They comprised the first of 27 drafts of

Newfoundlanders (and others) enlisted in the Newfoundland (from November

1917: Royal Newfoundland) Regiment to serve in ‘The Great War’, 1914 to

1918. (Not until May 11, 1918 was Regiment membership compulsory.)

Regimental records (as best can be interpreted) reveal ‘The First 500’ did

not include all of the first 521 volunteer recruits to be enlisted. Rather,

they were chosen from among the first 616 men; most of them native to the

Island of Newfoundland or Labrador, who signed to join the Regiment, at St.

John’s, in 1914. Although enrollment of volunteers began on August 21, 1914,

formal enlistment did not commence until September 1, 1914 (three days

before the 1914 version of the Regiment (first established in 1795) was

authorized by Newfoundland’s Volunteer Force Act). The first—and

only—volunteer enlisted on that date was eventually assigned Regimental No.

33. Among those enlisted on September 5, 1914 was the volunteer given

Regimental No. 1. Last of the volunteers to form part of the ‘First 500’

enlisted on 02 October 1914. He was assigned Regimental No. 616, and died in

combat at Beaumont Hamel.

More than a few enlisting volunteers overstated their ages when requested to

attest (swear) they were the required minimum enrollment age: 19 years.

(They didn’t have to produce their birth certificates.)

Of the 521 enlisted men, 386 (74%) were from St. John’s; 131, from 44 other

Island communities; one, from Labrador (Battle Harbour); 2 from England, and

1 from Quebec. (Later Newfoundland Regiment drafts—besides Newfoundlanders

and Labradorians (1 of them a Mount Cashel Orphanage resident)—included

adolescent and adult males from England; Scotland; British Columbia;

Ontario; Quebec; Nova Scotia; Portugal, and what was then Russia.)

Except for two officers (one—the operational commander—who left on October

2, 1914 on the S.S. Carthaginian, and another who departed on November 2,

1914 on the S.S. Mongolian) and 2 volunteers (who departed on October 24,

and November 2, 1914), the rest of ‘The First 500’—that is 20 of 22 officers

and 519 of 521 enlisted men—embarked for combat on October 3, 1914. At 4 PM

that date, they paraded from their Pleasantville tent training facility

(established September 3, 1914) to St. John’s Harbour, in stride with ‘The

Banks of Newfoundland’ (composed in 1820 by the Island’s then Supreme Court

Chief Justice, Francis Forbes). On the Harbour’s north side, at Furness

Withy Company pier, they crowded onto a passenger (sometimes sealing)

vessel, the S.S. Florizel (commissioned in Scotland in 1909 for 181

passengers), which had been converted to a troop carrier. By sunset, they

were transported to mid-Harbour; where Florizel anchored.

Some well-wishers who, on October 3, 1914, ringed the Harbour shores or

loitered on Harbour waters, lingered overnight and through the next day

during a long farewell. Not until 10 PM on October 4, 1914 did Florizel

weigh anchor and exit the Harbour, to join a convoy of Canadian contingent

vessels for a 10-day voyage to England; destination: Southampton (altered to

Plymouth during the voyage, for security reasons).

What happened to the First 500?

In England (on Salisbury Plain); later in Scotland (at Fort George,

Edinburgh and Stobs Camp), then back in England (at Aldershot), most of ‘The

First 500’ were further hardened for combat.

On August 20, 1915, by train and boat, the combat-ready portion of members

of ‘The First 500’ travelled to European battle theaters as part of the

British Expeditionary Force (BEF). They anticipated adventure. They

encountered anguish. Their first military engagement was at Gallipoli,

Turkey where, on September 23, 1915, they suffered their first combat

casualty (20 years old).

By then, and since, they have also been called the ‘Blue Puttees’. To

distinguish them from other BEF contingents, they were originally kitted

with dark blue cloth leggings known as ‘blue puttees’, apparently obtained

from the St. John’s Church Lads’ Brigade. (‘Puttee’ is from the Hindi term,

‘patti’, meaning ‘bandage’.) The puttees were later replaced, in Europe,

with khaki serge to conform with B.E.F service uniforms. (Contrary to

often-published myth, whether or not khaki serge was available in

Newfoundland when ‘The First 500’ were originally outfitted did not

influence the choice of blue puttees; probably intended to distinguish ‘The

First 500’ from other allied combat contingents.)

Of the 521 enlisted men, 41 would later return to St. John’s during World

War I, on furlough or duty; then, again, set out for military service in

Europe (France and Belgium). One of them did so twice. Among them, 18 had

been wounded (2 of them, twice) before returning to St. John’s and, after

arriving back in Europe, 8 of them were wounded, and 5 died: 3 in action,

and 2 from illness.

Thirty-one of the 521 enlisted men never engaged in military action with the

Regiment. They did not proceed beyond training (October 1914 to August 1915)

in England (1) or Scotland (30). They included the Regiment’s first

non-combat casualty (20 years old), who died from illness (pneumonia) on New

Year’s Day, 1915 at Fort George. The other 30 disengaged from the Regiment

either because their initial one-year term of duty expired and they chose

not to re-enlist with the Regiment, or they deserted, or were discharged as

medically unfit. Five of the 31, though, later transferred to, or enlisted

with, allied combat forces, and 1 joined the Newfoundland Royal Naval

Reserve.

The remaining 490 volunteers—among ‘The First 500’—saw combat. Among them,

151 died in, or resulting from, action. At Beaumont Hamel, 74 (including 1

classified ‘missing/presumed dead’) were killed and 6 later died from

Beaumont Hamel wounds. Elsewhere, 54 perished during battle (also including

1 reported ‘missing/presumed dead’) and 17 died from battle wounds.

Twelve of the 490 volunteers who performed combat duty were removed from

harm’s way by the enemy. They were captured in France (10 at Monchy in April

1917, and 2 at Mesnieres in December 1917). Eight of them had earlier been

wounded: 1 at Beaumont Hamel; 6 elsewhere, and 1, both at Beaumont Hamel and

elsewhere. The 12 captured volunteers remained prisoners of war for periods

of about 12 to 22 months. Not until January 1919 was the last of them

repatriated (after treatment, in Switzerland, for lingering combat injuries

and partial foot amputation by his German captors).

One of the 12 served on a committee which risked death by complaining

(successfully, in the result) to the enemy about their treatment while

imprisoned (principally, in what is now Poland). The ‘First 500’ officer who

debriefed them after the war became a Newfoundland lawyer in 1921. (The only

Newfoundland lawyer to serve with ‘The First 500’ was an officer who died of

Beaumont Hamel wounds.)

Among the 490 ‘First 500’ battle-active volunteers, 381 (78%) were

hospitalized at least once. (Included were: 122 hospitalized twice; 35 of

them, 3 times; 8 of them, 4 times, and 1, on 5 occasions.)

Of the 381 hospitalized volunteers, 230 were treated for war wounds (at

least 2 from wounds caused by ‘friendly fire’), consisting of: 80 wounded at

Beaumont Hamel, 112 wounded elsewhere, and 38 wounded both at Beaumont Hamel

and elsewhere. The other 151 hospitalized volunteers were treated for

illnesses, mostly incidental to combat (such as weather or horrific trench

conditions). But not all of the 381 hospitalized volunteers were released

following treatment. In hospital, 6 died from combat wounds sustained at

Beaumont Hamel, and 17 expired from battle injuries suffered elsewhere;

including 1 treated aboard a hospital ship and buried at sea. Some others

may have died from illness.

Fifty-seven of the 230 wounded ‘First 500’ volunteers sustained combat

injuries on multiple occasions (including 38 of those wounded at Beaumont

Hamel). Among them, 1 volunteer was wounded 4 times, and 2 others wounded 3

times.

Thirty-eight of the 230 volunteers hospitalized due to wounding either at

Beaumont Hamel (11) or elsewhere (27) were killed in combat after hospital

discharge. One Regiment member, hospitalized twice—for treatment of wounds

at Beaumont Hamel, in July 1916, and at Gueudecourt, France, in October

1916—was killed in action at Broembeek, France, in October 1917.

Of the 490 active Regiment volunteers, 132 were eventually assessed

medically unfit to continue combat (at least one of them due to blindness).

(One of those 132 later regained sufficient health to return from

Newfoundland to duty in Europe.)

Among all Newfoundland Regiment enlisted men engaged in the futile Beaumont

Hamel assault on July 1, 1916 (unredeemed by any territorial gain),

approximately 26 percent (80) of those who were killed or died of wounds or

were missing, and about 30 per cent (114) of those wounded, were from ‘The

First 500’.

Among the 22 officers serving with ‘The First 500’; 5 saw action at Beaumont

Hamel. None were killed there; although all were wounded, and 1 of them

later died from his wounds. Elsewhere during the war, 3 were killed; a

fourth died from war wounds, and 3 survived wounding. Fourteen of the

officers were hospitalized, due to wounding or illness (1 of them 5 times).

Two officers were discharged as medically unfit.

Remarkable is that any of the 22 ‘First 500’ officers survived the war. They

served with walking sticks and handguns (probably Webley Mark VI .455

revolvers). Their enlisted men, in contrast, were equipped with Ross rifles

or (from May 1915) Lee-Enfield No. 4 Mark 1 rifles; Lee-Enfield bayonets;

Mills Bomb grenades; and, in some instances, Stokes Trench mortars and

(eventually) Vickers Mark 1 heavy machine guns.

Only 32 of the 490 combat active volunteers among the Newfoundland

Regiment’s ‘First 500’ who saw action, and six of their 22 officers,

survived the war without being captured, wounded, hospitalized, or

discharged as medically unfit.

Of the 22 officers and 490 volunteers among ‘The First 500’ who fought: 4

officers and 8 volunteers were mentioned in dispatches by their superiors;

16 decorations were bestowed on 11 of the officers (1 of them being

decorated 3 times, and 3 of them, twice), and 41 decorations were presented

to 35 of the volunteers (1 of them 3 times; 4 of them, twice).

Newfoundland Regiment officers and volunteers totaling 591 are interred in

graves of uncertain location; including 12.5%—1 officer, and 73 volunteers

(42 of them killed at Beaumont Hamel)—from ‘The First 500’. (Some were

decimated in combat; and the remainder buried by allied forces or the enemy

in unmarked graves.)

Overall, among the 22 officers and 521 enlisted volunteers—543, in all—who

were ‘The First 500’: 31 (5.7%), all of them volunteers, never saw action;

512 (94.3%), including 22 officers and 490 volunteers, entered combat. Of

those 512: 395 (77%), including 14 officers and 381 volunteers, were

hospitalized; 238 (46.5%), including 8 officers and 230 volunteers, were

wounded, and 156 (30.5%), including 5 officers and 151 volunteers, laid down

their lives (in, or as a result of, combat). None of the 356 (69.5%) who

survived from among the 512 combat officers and volunteers—17 officers and

339 volunteers—or their families, were ever again, during their lives, able

to enjoy occasions “when the great red dawn is shining” (from British

lyricist Edward Lockton). Some of the survivors were blinded, crippled, or

lacked limbs. Many were severely substance (alcohol or medication) addicted.

All probably laboured, undiagnosed, from what now is called ‘post-traumatic

stress disorder’.

The last of ‘The First 500’ volunteers to survive the war died on July 21,

1993; age: 101 years. The last of the widows of ‘First 500’ volunteer

survivors of the war died in 2000; age: believed to be 108 years.

“The First Five Hundred” In Supreme Court

In Newfoundland, tears had not yet dried, and hearts not yet (if ever)

mended, when the former colony, by 1914 a Dominion of Britain, decided an

historical record needed be made of the service, suffering and sacrifice of

the Newfoundland Regiment, including ‘The First 500’, in World War I.

Granted, the first book about the Regiment’s exploits in ‘The Great War’ had

been published (probably in Toronto) in 1916 (and more recently, republished

in St. John’s by DRC Publishing). The author was a Regiment volunteer,

26-year-old John Gallishaw (not among the ‘First 500’). But his 135-page

book was limited, primarily, to an account of some aspects of the Regiment’s

service at Gallipoli, from September 1915 to January 1916. Newfoundland

wanted a much more comprehensive Regiment war publication.

Chosen for the task—in 1918—by the War History Committee of Newfoundland’s

Patriotic Association was Frederick A. MacKenzie (sometimes spelled

McKenzie), a Quebec-born author and London newspaper correspondent. The

basis for his knowledge of ‘The Great War’ is not readily apparent. In any

event, he produced nothing up to January 1920 (and when, in 1927, he did

provide a manuscript, the Committee rejected it).

By the start of 1920, however, a law student being mentored at the St.

John’s law firm of Squires and Winter had commenced work on an elaborate

(although not complete) war history volume limited to ‘The First 500’. He

was 30-year-old Richard Cramm, native to Small Point, Conception Bay.

By 1921, Cramm had completed The First Five Hundred of the Royal

Newfoundland Regiment, which he arranged to have printed in Albany, New

York: 114 pages of text (including 33 photos and eight maps) and 201 pages

of regimental records of 21 of the 22 officers and 519 of the 521 volunteers

in ‘The First 500’; as well as photos of most of them. (He included a

520thperson as a volunteer who, in fact, was the 22nd officer.) Most

probably, Cramm intentionally omitted at least one of two other volunteers

because he dishonourably separated (deserted) from the Regiment in Scotland.

He prepared the book “to chronicle briefly the military operations of the

heroic, fighting battalion that represented Newfoundland among the gallant

and victorious troops of the British Empire in the greatest war of history,

and to illustrate its persistent gallantry and splendid achievements by

reference … to conspicuous individual heroism” in performing “the most

solemn duty that has ever been thrust upon our country.”

Cramm’s effort to publish and sell the book is, in itself, a compelling

narrative.

Not flush with funds, Cramm found public support for publication and sale of

his book within Newfoundland’s government. This was not surprising. Senior

partner in the firm where he was studying law was the (controversial) Prime

Minister of Newfoundland: Richard A. Squires (from 1919 to 1923; and again,

from 1928 to 1932).

First: the Newfoundland government agreed to purchase 500 copies of Cramm’s

book, at $5.50 a copy, for a total of $2,750. Second: government advanced

Cramm $1,000.00 of that amount (from government’s ‘War Expenses’ account),

to assist him pay some of the book’s printing costs. Third: government

agreed to pay Cramm the balance—$1,750.00—when the book was printed and 500

copies were delivered to government. And, fourth: government waived customs

duties otherwise payable on the books when imported by Cramm from the

printer in Albany, New York.

In 1921, Cramm ordered printing of 1,500 copies of his book, for $4,500.00.

When the copies reached St. John’s from Albany, he promptly delivered 500 of

them to government, which then paid him the $1,750.00 balance of its

promised total financial assistance of $2,750.00. Cramm stored the remaining

1,000 copies in St. John’s; covered by insurance provided by Continental

Insurance Company.

On February 21, 1922—after Cramm had sold or gifted 369 of the 1,000 stored

copies of the book—fire damaged the remaining 631 copies. An insurance

umpire determined that Cramm was entitled, under the Continental policy, to

the cost he would incur to arrange reprinting of each of the 631 damaged

copies and, in addition, an allowance for the work invested by Cramm in

authoring the book ($1.33 1/3, per copy).

Continental was not amused. Legal action resulted in Newfoundland Supreme

Court. The Court decided, in 1922, that Cramm was entitled to recover from

Continental the cost of reprinting the 631 damaged copies of the book, but

nothing for his authorship.

Unknown is what amount Cramm eventually was compensated by Continental, or

whether he applied the amount received to have the 631 fire-damaged copies

of his book reprinted. Known is that in 2015, elite book publisher Boulder

Publications, of Portugal Cove-St. Philips, republished Cramm’s book at a

currently-reasonable price of $29.95 + HST.

For his part, Cramm, on April 2, 1923, was admitted to the Bar as the 150th

lawyer to be licensed to practice law in Newfoundland. He was still

practicing law, in St. John’s, in 1958 when he died.

The author has personal connections to the First World War.

Two of the author’s paternal uncles—brothers—both employed, before World War

I, sewing seats in men’s trousers at St. John’s, fought at Beaumont Hamel as

part of the Newfoundland Regiment’s C Company—not part of ‘The First 500’.

Both survived Beaumont Hamel, uninjured, though neither knew then how the

other had fared. One of the uncles, Private James Lewis Day (Regimental No.

1484), who enlisted 27 April 1915 at age 19, later died in combat 23 April

1917, at Les Fosses Farm, near Monchy, France (where he was buried in an

unmarked grave). His brother Private Walter Bennett Day was hospitalized in

London when he received the news that James was killed. He replied

(mistakenly), “I know. He died at Beaumont Hamel.” Walter (Regimental No.

1660) enlisted 19 June 1915 at age 15; giving his name as Walter Valentine

Day because he was born on Valentine’s Day. (Identification such as birth

certificates were not required to enlist in the Regiment.) He served as a

Regimental drummer. He survived the war; but when demobilized on 15 January

1919, he was profoundly damaged psychologically by what he had endured

during combat. He was among the first patients admitted to the Caribou

Pavilion, General Hospital, St. John’s. He died on 18 November 1982. The

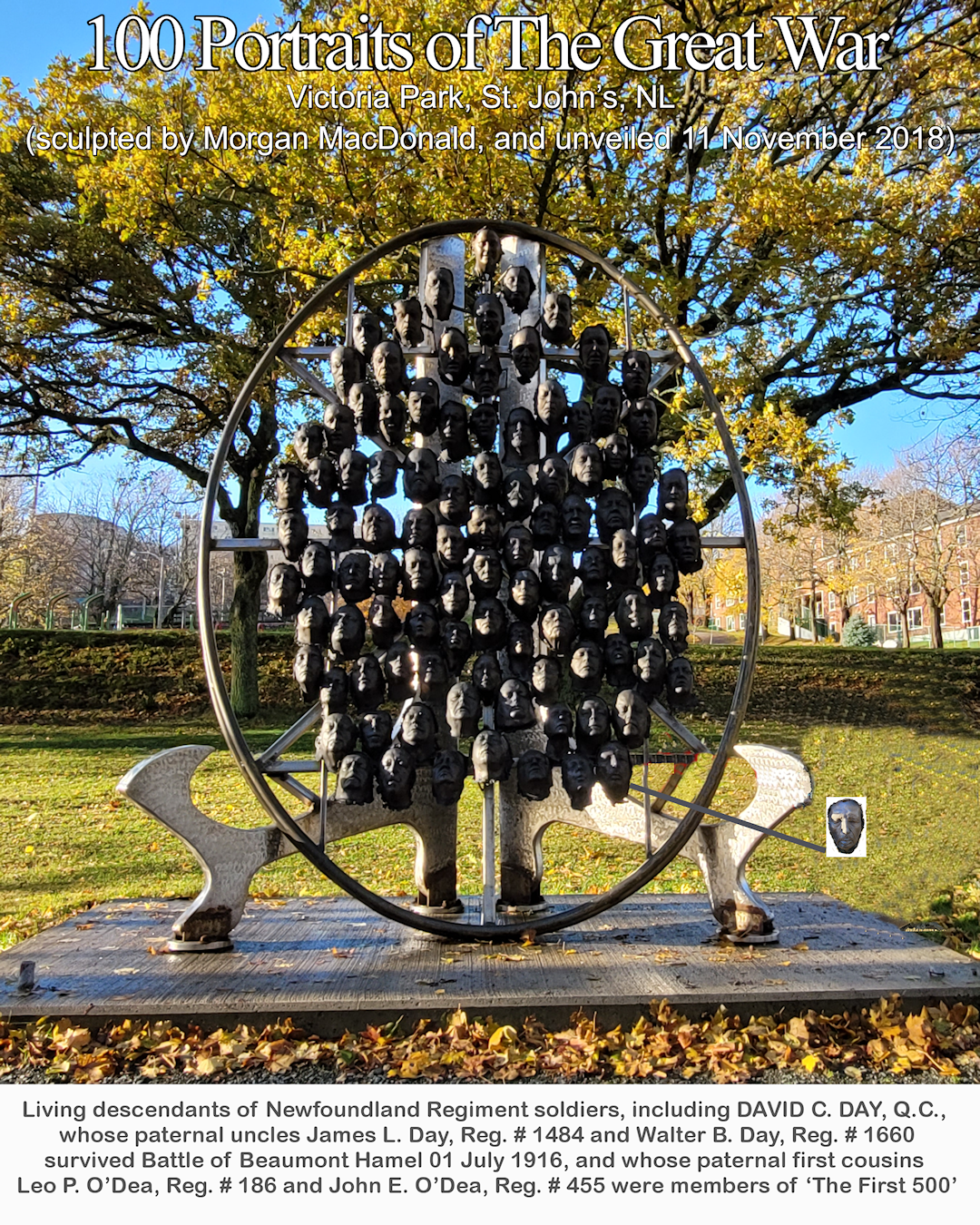

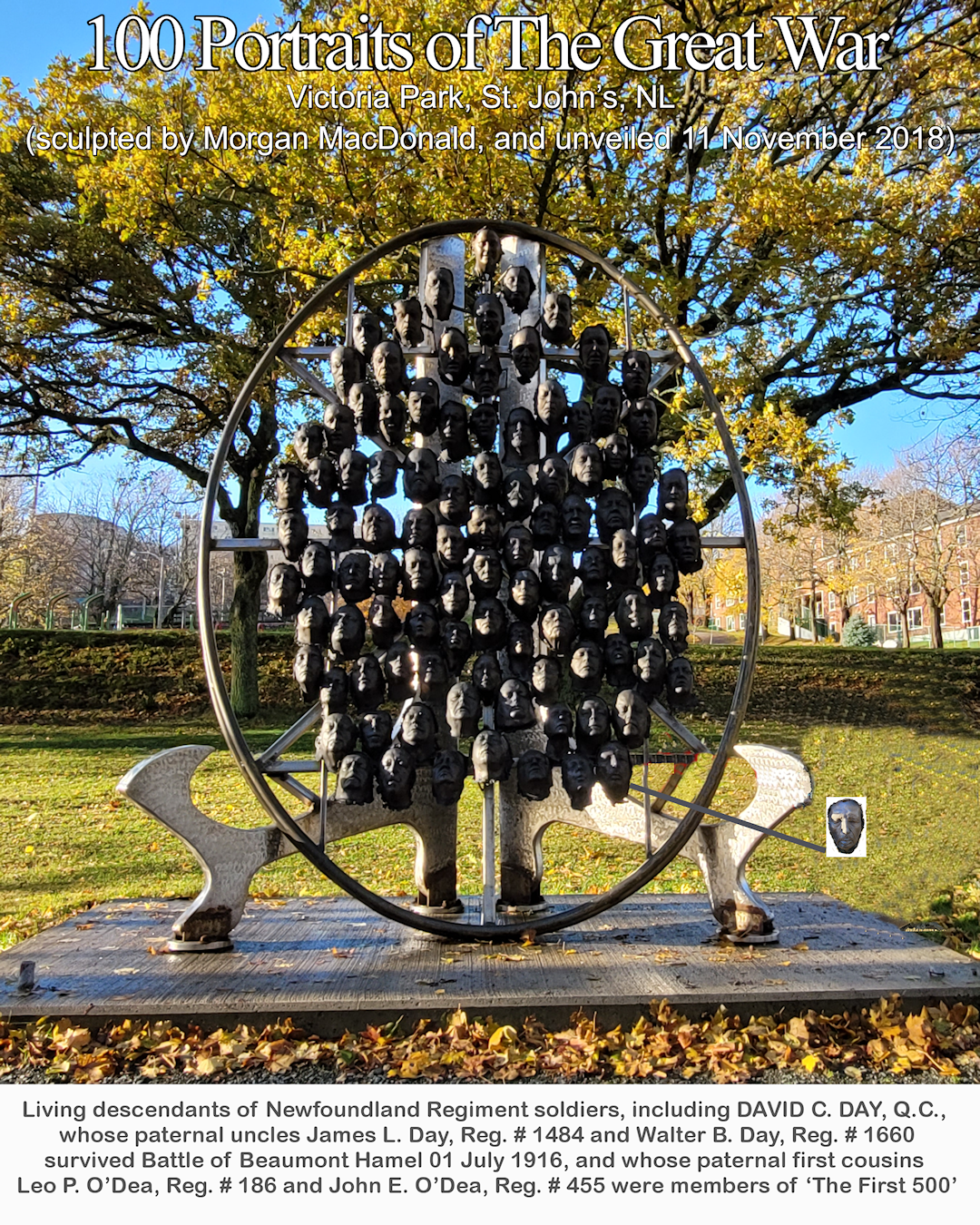

author, in memory and honour of his two uncles, volunteered his face for A

Hundred Portraits of the Great War, forged in bronze by eminent Newfoundland

sculptor Morgan MacDonald.

Two second cousins were among Newfoundlanders who served in ‘The First 500’

during World War I. Both were sons of John Day, a St. John’s, NL Protestant

who, following marriage to a woman of the Roman Catholic faith, changed his

surname from Day to O’Dea. One of his sons who served in World War I was

Private John Eugene O’Dea (Regimental No. 455). He enlisted 08 September

1914, and was demobilized 05 March 1919. He was available for combat for

only part of World War I. The reason was that he spend part of the war in

prison; but not as a prisoner of war. He was, in Scotland, convicted 23

October 1917 of the criminal offence of bigamy—for having, 04 September 1916

at Ayr, Scotland, wed a Scottish woman, while having a wife in St.

John’s—and sentenced to 18 months imprisonment. The other of John (Day)

O’Dea’s sons who served in World War I was Private Leo Patrick O’Dea

(Regimental No. 186). He enlisted 04 September 1914, and was demobilized 15

February 1919. He was wounded at Beaumont Hamel, France, on 01 July 1916,

and again wounded at Mesnieres, France, on 30 November 1917. During his

World War I service, he was promoted from Private to Lance Corporal, then to

Acting Corporal, and ultimately, to Acting Sergeant.

The author, a practicing Barrister at St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador

since 1968, and a Master of Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador since

2010, was junior law partner, at Lewis, Day Law Firm, of Hon. P. Derek

Lewis, Q.C. When, on 19 January 2017, Lewis, Q.C. passed, he had practiced

law longer (69 years, 3 months and 3 days) than any other lawyer, anywhere,

at any time.

JUDGE John L. Joy

16 September 2021

WALTER OWEN BOOK PRIZE

History and 2021 Recipients

Canadian Foundation for Legal Research

University of Calgary, Faculty of Law

CHIEF JUSTICE J.V.H. MILVAIN

VISITING CHAIR IN ADVOCACY:

42ND ANNUAL PROGRAM, PRESENTED BY

SUPREME COURT OF CANADA JUSTICE SHEILAGH MARTIN,

JANUARY 2021

Excerpt from presentation by David

C. Day, Q.C.,

formerly, Faculty of Law Chair In Advocacy

Should Memorial University Establish A Law School ?

“Good Judgment: Making Judicial Decisions”

Walter Owen Book Prize – 2019

Canadian Foundation For Legal Research

Dalhousie University Schulich School Of Law — Class Of 1967:

Fiftieth Anniversary Reunion, Halifax, NS, 15-16 September 2017

Graduates of Dalhousie University Schulich School

of Law Class of 1967 who attended the 15-16

September 2017 reunion, in Halifax, NS, to mark the 50th anniversary of

their graduation,

included (left to right): David B. Ritcey, Q.C.; Ronald B. Twohig, Q.C.;

John M. Hanson, QC.;

Edward Raymond, Q.C.; John G. Cooper, Q.C.; Arthur F. Miller, Q.C.; Hon.

David Cole; Thomas J.

O'Reilly, Q.C.; Diane Daley-Campbell; David C. Day, Q.C.; Hon. Leo D. Barry,

William C. West; Hon.

George Mullally; Alan D. Hayman, QC.; Jack C. Lovett, Q.C., and Hon. Norman

Carruthers.

Dalhousie Schulich School of Law – Class of 1967

Notes for Address at

Unveiling of Plaque from Class of 1967,

16 September 2017, 11 AM, Halifax, NS

Tribute to:

HONOURABLE P. DEREK LEWIS, Q.C.,

1924 to 2017

Old Tome Speaks Volumes

The

Telegram, St. John's, NL

09 July

2015

At Last Defence Lounge at the University of

Calgary on June 5, my lunch was interrupted by a hand holding a book,

which descended over my left shoulder. The owner of both said, “you may

be interested in this.”

The book was a dark-wine covered 1901 edition of

the “Manual of the Constitutional History of Canada,” by Sir. J. G.

Bourinot. Its owner, Jean-Paul Boyd, eminent Vancouver lawyer and

executive director of the Canadian Research institute for Law and the

Family, had purchased the book for $2 at a Calgary flea market within

the previous month.

Pasted onto the flyleaf were library decals of

the book’s two prior owners: R.A. Squires, Newfoundland’s prime minister

(1919-23 and 1928-32), and Joseph R. Smallwood, premier (1949-72). Not

that either of them ever needed or heeded a scholar’s constitutional

advice, the book’s only three marked passages are reminders of how both

governed.

At page 167: “The premier is the constitutional

medium of communication.” Arguably, both Squires and Smallwood sought to

be their governments’ only communicators.

At page 168: “ … if there be a difference of

opinion between the premier and any of his (cabinet) colleagues, the

latter must resign.” Several Smallwood administration cabinet ministers

tell me that when appointed minister, each was required to sign a

resignation letter which Smallwood could, and did, act upon if they

dared to differ in cabinet — or even if Smallwood was dissatisfied with

the intensity of their cabinet support.

At page 176: “ministers are not absolutely bound

to introduce particular measures commended to the consideration of (the

legislature)” in the speech from the throne. Squires and Smallwood were

not our only political masters to rely on that constitutional opinion.

Have satisfied myself that the book had been

lawfully acquired, I gratefully accepted it.

David C. Day,

Q.C.

St. John’s.

LAW AND MENTAL DISORDER

Bloom,

Hy, and Schneider, Richard D., Eds., Law And Mental Disorder[:] A

Comprehensive And Practical Approach (Toronto: Irwin Law, 2013), i-xxi,

1,422 pp.

Reviewed by: DAVID C.

DAY, Q.C.

(01

July 2015)

Four Hundred Years Of Law Reporting In Newfoundland and Labrador

By

David C. Day, Q.C.

Remarks to National Judicial Institute Symposium: Trinity400,

Trinity, NL, 04 June 2015

Assessment of Lawyer’s Invoice for Fees

and Disbursements

by Newfoundland and Labrador Supreme Court

First Encounter of Canadian Charter of

Rights and Freedoms

(In Force: 17 April 1982) In Canada’s Courts:19 April 1982

Ray David George Guy

1939 - 2013

By David C. Day, Q.C.

(Colleague of Ray Guy at The Evening Telegram, 1963-1967)

Published in The Telegram, 05 June

2013

Thanks

for the joyful Telegram memories

Before Ray David George Guy (1939-2013)—celebrated social and political

commentator, book author, and playwright—left his childhood home in Arnold’s

Cove (eight kilometers from his birthplace, Come By Chance), he chose writing as

his adulthood vocation. He was largely influenced in his career decision by

Joseph R. Smallwood Liberals’ resettlement program (which, from 1954 to 1975,

relocated almost 30,000 persons from some 300 villages). He was, he said, deeply

troubled by grief the program caused his fellow rural Newfoundlanders.

He employed humour as a weapon to express his dissent from the provincial

government’s decisions to create and implement the program. In particular, he

ridiculed its architect, Premier Smallwood, for that program—and much else the

Premier advocated. His principal vehicle for heaping scorn on the Premier was a

daily (weekday) column in The Telegram (then, The Evening Telegram) from about

1963 to 1974.

During part of this period (about 1963 to 1972), his writing served as

opposition—sometimes the only substantial challenge—to Smallwood’s provincial

government administrations. And, for the remainder of this period (1972 to

1974), he wrote irreverently about Smallwood’s successor, Premier Frank D.

Moores (whose electoral success was, in no small part, a product of Guy’s

columns).

Motivated, significantly, by the domestic resettlement program to become a

journalist, Ray Guy’s acerbic writer’s art was materially impacted by the

American humourist, S.J. Perelman. Like Perelman, he was adept at piercing

“through to the heart of pretense and conceit”.

Years later, Guy yearned for a particular Perelman anthology (his

contributions to The New Yorker magazine) which I found in Foyle’s Bookshop,

London, and sent to him.

Guy occupied a desk at the back of The Telegram’s newsroom, when located in the

Parland Building, 271-275 Duckworth Street. Typically, he commenced each

matchless weekday column about 1:30 PM. Using an Underwood, later a Remington,

manual typewriter, he would continue to be engrossed, in crafting a column, at 6

PM—often, until much later.

He brooded and troubled over each word, each sentence. His painstaking

choice of language was as precise as the wielding by a surgeon of a scalpel in

an operating theatre. He teased each paragraph, slowly and cleverly, from his

droll mental hard drive.

Often, he consulted, on this or that turn of phrase, with newsroom colleagues:

Mary Deanne Shears, the women’s editor (later, managing editor of The Toronto

Star), and Mary Deanne’s understudy, Jane Williams; news reporters Joe

Walsh, Don Morris,

Ron Crocker (later, a C.B.C. regional director), Gary Callahan, George Barrett,

and Frank Holden (now a playwright); sports department writers Bob Badcock, Pee

Wee Crane and Ron Rossiter; editing desk staff Bob Ennis (later, of The Montreal

Gazette), Maurice Finn, and Tommy Power, and Canadian Press correspondent David

Butler.

Because he regarded Premier Smallwood as fancying himself a Messiah, Guy seized

on every opportunity to capitalize pronouns, within sentences, referring to the

Premier. Invariably, the editing desk detected and lower-cased them.

Torpid summer afternoons in The Telegram newsroom were memorable for Guy’s

arrival, barefoot, ferrying ten pound watermelons; which he distributed to

colleagues, employing a lobster knife secreted in his desk.

Assigned, one summer morning, to report on Carolyn Hayward, a bullfighter in

Spain—who was rumoured to be disembarking a vessel in St. John’s Harbour for a

visit to her native St. John’s—I approached Guy, seeking advice on interviewing

her. He offered to accompany me. Together, we walked both sides of the

waterfront, and boarded each moored vessel, in search of our quarry. Hours

later, we identified a woman leaving a ship.

We

hailed her and learned her given name was “Carolyn”. Our 4.25 by 5.5 inch

newsprint pads in hand, we commenced questioning. Clear from her responses, the

woman was not a bull fighter. Rather, she gained her wages from retailing

physical intimacy. We made the recounting of her harsh life the subject of a

feature story we left on the editing desk about 2:30 AM.

Later that morning, we were escorted one floor up to The Telegram’s executive

offices to be chastised by then-management.

Within a month, we were back in the executive suite—to explain why we had

devoted a full night to drafting an unassigned story entitled, “St. John’s After

Dark.” My personal papers include drafts of this imaginative, occasionally

fanciful, account of nocturnal St. John’s. Guy was proud of the lead sentence

(here published—at long last—for the first time): “Twinkling lights, in a

variety of hues, festoon the slate grey shores of the ancient, sheltered harbour

at St. John’s, like a necklace of precious and semi-precious trinkets. Beneath

them, the city throbs, pulsates, bustles, and—in some precincts—moans.”

Assigned to report an event in Bishop’s Falls, Guy and I missed the late

afternoon train from St. John’s. At alarming speeds, he tooled his green coupe

to Holyrood station. At first, a police stallion, then a police cycle, and

eventually a police car pursued him. Guy eluded all comers. On arrival in

Holyrood, he concealed his vehicle in a copse of poplars on private property,

and we caught the train as it chugged from the station.

We suited up in blue turtleneck sweaters and berets, and accessoried ourselves

with pince-nez spectacles, on arrival in St. Pierre, for another assignment—to

report on rumoured insurrection. Although, as Guy cautioned, we made our

inquiries discretely, we attracted attention of gendarmes. They briefly detained

us and relieved us of our notepads.

In 1965, the

Province received a gift from the Portuguese Fisheries organization: a statue of

navigator Gaspar Corte-Real. Premier Smallwood proclaimed that an elaborate

unveiling was in store. Guy discovered the gift, crated and wrapped in

tarpaulins, lying beside Confederation Parkway. “The unveiling,” Guy announced,

“will be sooner, not later.” He and a junior reporter (who will remain nameless)

made a late night visit to the Parkway, unpackaged Gaspar—with aid of tire iron

and grapnel—and took a ‘snap’ which appeared next afternoon in The Telegram.

Guy was not a

fervent adherent of organized religion.

But, his conversation was often punctuated with brief liturgies from the

Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer.

And, during summer lunch hours, at least, twice monthly, he and I

accompanied reporter John Fraser (later, Master of Massey College, Toronto) to

the Anglican Cathedral in St. John’s.

There, we were Fraser’s only audience as he performed hymns, movements,

and dirges, on the Cathedral’s Robert Hope-Jones/Casavant organ.

Although impish and ever receptive to join in capers, Ray Guy, by nature, was

shy, private and understated. When I paid him a visit in 1975, he was

preoccupied, typing and re-typing a short letter on newsprint copy paper. The

letter consisted of a single sentence. He planned to deliver the letter to the

workplace of Cathy Housser; recently arrived from British Columbia to serve as a

C.B.C. producer in St. John’s. Whether he delivered the proposal, I am not

aware. Within six months, however, Ray and Cathy were married.

Guy

quoted, with ease, passages written by his ‘mentor’, S. J. Perelman. More than

once, he reminded me of Perelman’s sentence that “love is not the dying moan of

a distant violin—it is the triumphant twang of a bed spring.” When we reminisced

about chasing the ‘bullet’ to Holyrood, he recounted Perelman’s narrative, “The

whistle shrilled, and in a moment, I was chugging out of [New York] Grand

Central [station] … I had chugged only a few feet when I realized that I had

left without the train, so I had to run back and wait for it to start.”

Asked by a C.B.C. radio interviewer, in 2008, whether he had any regrets,

he replied “none”. While Guy was a reporter and columnist at The Telegram,

he lived faithful to the creed, life is not a dress rehearsal. In fact, some of

his columns were written in the format of theatrical scripts.

Ray Guy’s enduring legacy is a cold type footprint of priceless,

published commentary, authored by a rare wordsmith genius; serving to entreat,

exasperate, educate, enrich and entertain.

Thanks, Ray—for the memories. Thanks for the indelibly joyful Telegram

memories.

David C. Day, a Telegram reporter from 1963 to 1967, writes from St. John’s.

An Anecdotal History Of The Newfoundland

Supreme Court

And Its Chief Justices

[Among the most erudite, philosophical, and clever—not to mention, droll and

whimsical—of the 25 Chief Justices of the Newfoundland and Labrador Supreme

Court was Noel H.A. Goodridge. He was appointed a Justice of the Trial Division

of the Court on 13 November 1975, and to Court of Appeal as Chief Justice of

Newfoundland and Labrador on 17 November 1986. He assumed supernumerary status

on 01 January 1996. He died 12 December 1997. Go >Authors for the text of his

remarks to the Provincial Court Judges' Association, St. John's, in October

1991; as recently published in Hearsay, a publication of The Law Society of

Newfoundland.]

Decisions

R. v. Woodrow [James]

Provincial Court of Newfoundland and

Labrador

sitting at Nain, Labrador

Joy [John], P.C.J.

29 July 2011

Vikas Khaladkar, for Her Majesty The Queen

David C. Day, Q.C. for Accused

Authors

Binding Bargains

Solicitor agreement in matrimonial matters

From the dawn of legal memory, solicitors'

agreements have typically bound their clients if

litigation was pending or in progress. David C. Day, Q.C. asks whether that

abinding common

law principle has been compromised by provincial matrimonial legislation which

provides that

domestic agreements are unenforceable unless reduced to writing, signed by the

contracting

parties, and witnessed. Answer: no, because the legislation lacks "irresistible

clearness."

[Federated Press, Montreal, 1994]

Preventive Justice

Preserving the peace (Part 1)

As a process dedicated to preventive justice, the "peace bond" provision of the

Criminal Code

(described formally as a "recognizance" under section 810 of the Code) is unique

in Canada's

penal law, as it involves neither charge, nor plea, nor fmding of guilt or

conviction. In the first of

three articles about legal processes intent on helping to preserve peace and

security in and

between families (inter alia), David C. Day, Q.C. describes the function of the

"peace bond".

[Federated Press, Montreal, 1996]

Preventive Justice

Preserving the peace (Part 2)

Preserving the peace (Part 2)

Even if a court declines an application to require a person to enter into a

recognizance to keep the

peace under the Criminal Code's "peace bond" provision (section 810, discussed

in part 1 of this

series), the court may resort to its common law jurisdiction to obligate the

person to peace keep.

David C. Day, Q.C. appraises exercise of this jurisdiction, in the service of

preventive justice

(together with several of the Criminal Code provisions, other than section 810,

that likewise

specifically contemplate peace-keeping). [Federated Press, Montreal, 1996]

Preventive Justice

Preserving the peace (Part 3)

Legal mechanisms for preserving the peace are not furnished exclusively by

Criminal Code

provisions and common law (discussed in parts 1 and 2 of this series). As David

C. Day, Q.C.

outlines (in his third, and final, article on the subject), provincial and

territorial legislation and

the equitable concept of parens patriae serve vital functions in peace

preservation, sometimes in

partnership with common law and Criminal Code. [Federated Press, Montreal, 1996]

Child Protection

Sauce for the goose ls sauce for the gander

In the wake of the Supreme Court of Canada's 1991 decision in R.v. Stinchcombe

requiring

Crown disclosure of its case to the accused in criminal prosecutions, courts

have imposed on the

state and state agencies responsible for child protection a duty to disclose

their cases to parents

and other guardians of children involved in protection proceedings. Moreover, as

David C. Day,

Q.C. determined, the extent of disclosure depends on whether the protection

proceeding derives

from exigent circumstances, and the duty to disclose is not confined to the

state. [Federated

Press, Montreal, 1994]

Evidence

Opinions of learned treatises as shield and saber

Treatises have customarily been used to attempt to enhance or impugn the expert

witness's

knowledge or methodology or conclusions. In what circumstances may opinions of

authors of

learned scientific treatises, where the authors are not themselves present in

court, be cited to an

expert witness? Or, be admissible in evidence? And, to what extent may such

opinions be

introduced to enhance an expert witness's conclusions on examination-in-chief?

Or, to impeach

the expert witness on cross-examination? These and related questions are

addressed by David C.

Day, Q.C. in his commentary on learned treatises as shield and saber. [Federated

Press, 1997]

Perils in Practice

Taxing ordeals of solicitor accounts

Agony associated with collection of some solicitor-client accounts is

occasionally preceded by

audit and approval hearings that determine the sum a solicitor is entitled to

attempt to collect.

David C. Day, Q.C. writes that data storage capacities-in computer and computer

disk

memory-reinforce the requirements for integrity and accuracy in the accounting

and billing of

fees. [Federated Press, 1997]

Family Law

Perils in Practice

Taxing ordeals of lawyer income tax returns

Although a family lawyer was substantially successful in a Tax Court of Canada

appeal from

administrative treatment of his Tl General income tax returns for three years,

the Court ordered

him to pay solicitor and client costs. Moreover, costs were authorized on the

infrequentlyallowed

higher solicitor-and-client scale. David C. Day, Q.C. explains that the Court's

reasons

combine insights into treatment-under income tax law, procedure and practice-by

the Minister

of National Revenue of tax returns of privately-practicing lawyers. Although the

decision producing

appeal occupied seven days, the case "boiled down essentially to a number of

factual

issues that," the Court felt, "could and should have been resolved at the

assessments level or the

[administrative] appeals level." Permeating the decision was the Court's dismay

at repeated

failings of the taxpayer to responsibility access these extra-judicial

processes. The decision (i)

affords insights on income tax law, procedure and practice treatment of tax

returns of solicitors

practising privately in Canada, and (ii) offers counsel about how taxpayers

should not treat the

Minister. [Federated Press, 1998]

'Lest We Forget'

While browsing in a St. John’s bookstore (Downhome), two years ago, I discovered a copy of Lieutenant Owen William Steele of the Newfoundland Regiment, edited by historian David R. Facey-Crowther. I chanced to open the book at page 189. There, I read the last entry in Lt. Steele’s diary of his World War I experiences. Dated Saturday, 01 July 1916, the entry was a copy of his typewritten report, addressed “To the Adjutant”, of “the names of men of D Company [of the Newfoundland Regiment], who went over parapet on July 1st, and returned unwounded.” Among the 16 listed Regiment soldiers were J. Day (Reg. # 1484) and W. Day (Reg. # 1660); two of my paternal uncles. The effect of the report was that both had survived the Battle of the Somme at Beaumont Hamel.

My uncle James Louis Day was born in St. John’s on 23 March 1898. He enlisted in the Newfoundland Regiment in 1914. He was 16. Enlisting at the same time was his brother, my Uncle Walter Bennett Day, born 14 February 1900. He was 14. By accident or design, Walter overstated his age. His superiors discovered this fact when or shortly after the Regiment, en route from Newfoundland to combat in Europe, reached Scotland. There, Walter was temporarily relieved of duty and sent to grammar school. In due course, he rejoined his Regimental mates.

(Walter is aptly described by the title of war historian Gary Browne’s latest (2010)—illuminating, insightful—book, Fallen Boy Soldiers.)

Whether (as several war veterans later recalled to me) Walter served as drummer, while Regiment members exited their trenches, about 9:15 AM on 01 July 1916, to see action at Beaumont Hamel, I was never able to determine from him. Whenever I later asked him, he became crestfallen and was speechless.

What John Crosbie, Q.C. has aptly described as “the ferocity of combat” that summer morning, is recreated by G. J. Meyer in his June 2006 history, A World Undone [:] The Story of the Great War 1914 to 1918:

At Beaumont Hamel nine out of every ten members of a Newfoundland battalion advancing toward the Hawthorn Ridge crater were shot down in forty minutes. …. Before it was over the German gunners, at points in the center where the carnage had been most terrible, found themselves unwilling to continue firing. Shutting down their guns, they watched in silence as the British [and Newfoundlanders] departed with whatever wounded they were able to take with them.

Both James and Walter were among 68 Newfoundlanders who answered the roll call next day (my birthday). 733 other Newfoundlanders – wounded or dead – were less fortunate. (The wounded included Lt. Steele’s brother, James.)

On 07 July 1916, Lt. Steele (Reg. # 326) was himself wounded at a battlefield headquarters building. He was resuscitated and conveyed to hospital by my Uncle Walter and other Regiment soldiers (based on oral history passed down to his namesake, nephew William Steele of Winnipeg). Lt. Steele died of his wounds on 08 July 1916. In its edition of the same date, a St. John’s newspaper lamented: “St. John’s is weeping for her dead and wounded. What can comfort her? Even peace cannot dry her eyes. Time alone may heal such wounds.”

On 21 April 1917, my Uncle James optimistically wrote to his parents Sarah and Ernest, Hayward Avenue, St. John’s. “I don’t think the war will last much longer. We give it, out here, until July [1917], …. And if God spares me to come through alright, I will be home to you before Christmas.” Although his optimism was misplaced, he was not to know. Two days later, he died in action at Arras, France.

Regiment Captain Leo C. Murphy dedicated his poem, Remembrance, written on Bell Island in April 1925, to James, who had served as orderly to Capt. Murphy (and to his Platoon Sergeant Richard Neville):

Last night I saw the sunset fires

Sink in the dark’ning West,

While save the chill winds ghostly sigh,

All lay in tranquil rest.

And standing ‘mid the shadows dim,

My restless thoughts had flown,

Where two – real, loyal soldier lads,

Sleep their last sleep alone.

Wounded in action shortly after Beaumont Hamel, Walter was transported to England and hospitalized. When a visitor to Walter’s bedside, in April 1917, brought news of James’ death, Walter replied that he already knew. He told the visitor that James died at Beaumont Hamel. Evidently, Walter and James hadn’t seen each other since they scaled the parapet, there, on July 1st, 1916. And, they hadn’t heard each other answer the roll call next morning.

After returning to St. John’s, Walter briefly operated a cobbler’s shop. But the impact of the Great War had permanently damaged him psychologically. For many years, he was sheltered and cared for by his sister (my aunt) Stella Day Hunt (seamstress to Government House). And, he was among the first patients admitted to the war veteran’s wing of the General Hospital (now part of the Leonard A. Miller Centre for Health Sciences), Forest Road, in the 1960s. He died in St. John’s, while still a patient, on 18 November 1982.

Every July 1st and November 11th, I pause to remember the sacrifices, in the Great War, of my uncles James and Walter, and their comrades, of the Newfoundland Regiment: while holding the soldier’s photograph of Uncle James and the medals of Uncle Walter—lest I forget.

(Portions of this article, by David C. Day, Q.C., were published in The Telegram, St. John’s, NL, 11 November 2006. Acknowledged in preparing this entry to the Current portal is the assistance of Karen Day- Workman, Fredericton, NB.)

View "And In The Morning", Featuring Walter Day, RNR # 1660

Authors

What are the implications of Supreme

Court of Canada's 2009 decision--relating to health care choices by 'mature

minors'--in A.C. v. Manitoba (Director of Child and Family Services)? Counsel

for A.C. offers his opinion in "Getting Respect: The Mature Minor's Medical

Treatment Decisions" (2010), 88 Can. Bar Rev. 671. For the full text of his Case

Comment: [View]

For an earlier opinion by the same author, on the subject of 'mature minors',

see: "The Capable Minor's Healthcare: Who Decides?" (2007), 86 Can. Bar Rev. 1:

[View]

54 Years Ago: September 1962

FIRST ST. JOHN'S TO PORT AUX BASQUES

WALK ACROSS ISLAND OF NEWFOUNDLAND

September 2, 1962

Kenmount Road

(outside Newfoundland Tractor Co. Ltd),

St. John's, NL

[Left to right] David Day, Frank Janes Jr., Bob

Lemessurier

September 20, 1962

Trans Canada Highway

(at entrance to Port Aux Basques

[Left to right] David Day, Frank Janes Jr., Bob

Lemessurier

Ethics

Remarks to

National Family Law Program,

16 July 2010, Victoria, B.C.

David C. Day, Q.C.

[Page numbers in the Remarks refer to 2010 paper at:

http://www.lewisday.ca/ethics.html.]

“Around half past two o’clock … [in] the morning … , …, a

middle-aged attorney … was awakened by the ringing of his bedside telephone. ….

The call, …, was a business one, and although it was from an undertaker, it did

not turn out to be bad news.”

So begins an instructive, not to mention indelible, account of “The Rich Recluse

Of Herald Square” in The New Yorker magazine. (31 October 1953, p. 39)

The magazine article—recommended, for the taking, from our presenter’s

table—recounts the tumultuous challenges of determining when a lawyer is

retained. More significantly, the article narrates the wrenching tribulations of

the retained lawyer, in striving to ascertain the true identity of the retaining

client, and whether that client was competent to give instructions.

After all, “the rich recluse of Herald Square”, in New York City, was 93 years

old; had rarely ventured outside her two-room hotel suite in 25 years; sustained

herself on evaporated milk, coffee, crackers, bacon, eggs, and “an occasional

fish” which she consumed raw; limited her attire to a towel rarely laundered;

was blind and severely hearing-impaired hearing; and constantly nurtured her

face with petroleum jelly.

Knowing whether you have a client and, if so, who the client is, and whether the

client is competent to instruct you are—indisputably—essential, rudimentary

tasks each lawyer must discharge at outset of each retention. They are initial

tasks integral to responsibility—this panel’s subject—in the law vocation.

Practising law is a vocation, my learned friend James J. Smythe, Q.C., of St.

John’s assures me, is a daily exercise in “lurching from crisis to crisis.” And

a vocation, another of my learned friends from St. John’s, Lewis B. Andrews, Q.C.,

is convinced, in which “lawyers, not infrequently, are more troubled by

retention subjects than their clients.”

Responsibility comprises three elements: ethical, legal and professional.

For the full text of the Remarks:

[http://lewisday.ca/ethics.html]

Media Links

A law firm partner attended the

reunion (06-07 August 2010) marking the 50th anniversary of his graduation from

Prince Of Wales College.(100th Graduating Class) A trove of back issues (1898-1987) of the College's

magazine--The Collegian (every Page, every Photo, including every article)--is maintained by Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Click

on the link, then click on magazines, then choose

The Collegian, at this link:

http://lewisday.ca/medialinks.html.

Commended for superb reunion planning are: Robert Jenkins, Patricia (Boone)

Jenkins, Barry Sparkes (former Registrar of Newfoundland and Labrador Supreme

Court), Margot (Peters) Evans, Barbara (Allen) Stone, Judi (Snelgrove) Somers,

Joan (Lester) Chapman, Lorraine (Best) O'Neill, Marilyn (Duffett) Pumphrey, and

Pauline (Stanley) Wadland.

Decisions

Cases in which Lewis, Day is, currently, retained as counsel, and other current developments, include:

Newfoundland and

Labrador Supreme Court [Trial Division]

Lawrence and Kent

[Counsel: Lewis, Day] v. Her Majesty The Queen

[File no. 2006 /

01 T 1532 - application to 'stay' indictment in response to alleged police

misconduct - argued 16 and 17 October 2006 -Judgment 24 October 2006 by Halley

J.: police conduct in performing criminal investigation unacceptably prolonged,

incompetent, constituted dereliction of duty; collectively amounting to abuse

of process - decision on application for 'stay' indictment deferred to end of

jury trial - Notes: both accused acquitted 01 December 2006 after 30-day jury

trial; publication ban has been lifted]

European Court Of

Human Rights

[Strasbourg]

Case Of Jehovah's

Witnesses Of Moscow v. Russia

[File no. 302 / 02

- appeal for redress under Article 34 of the Convention for the Protection of

Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, due to alleged breaches of Convention

human rights - Judgment 10 June 2010: allowing, substantially, appeal by

Jehovah's Witnesses Of Moscow - Notes: John M. Burns, of Kelowna, BC,

international constitutional lawer, was among counsel for Jehovah's Witnesses Of

Moscow; David C. Day, Q.C. of Lewis, Day, St. John's, NL, was among counsel

consulted by Jehovah's Witnesses of Moscow.]

Supreme Court of Canada

A.C. [Counsel: Lewis, Day] v. Manitoba (Director of Child and Family Services)

[S.C.C. File no. 31955 - argued 20 May 2008 - judgment 26 June 2009:

Charter issues dismissed; otherwise allowed with costs to A.C. of all

Manitoba and S.C.C. proceedings]

Newfoundland and Labrador Supreme Court [Trial Division]

[B.(D.)] [Counsel: Lewis, Day] v. Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennslyvania,

[New York, Inc., and Canada] Counsel: Lewis, Day

[File No. 2006 01 T 1676 - preliminary applications to dismiss proceeding - argued 09 April 2008;

judgment 29 October 2009 by Green C.J.T.D., proceeding dismissed with costs]

Newfoundland and Labrador Supreme Court [Trial Division]

P.H. v. Eastern Regional Integrated Health Authority and S.J.L.

[Lewis, Day appointed counsel for S.J.L.'s 'Best Interests']

[File No. 2009/ 01 T 5556 issue whether adolescent S.J.L. competent to make own health care decisions

- argued 10 February 2010 - judgment of LeBlanc J. 17 February 2010: not competent]

Ethics

W. GLEN HOW, Q.C. – IN MEMORIAM

I Remember Glen How

The Globe and Mail, Toronto,

26 February 2009

For most of the 65 years he practised law—most-recently in Georgetown, ON—W. Glen How Q.C. maintained a modest wooden lecturn, from which he painstakingly rehearsed trial and appellate arguments for cases he conducted in every Canadian province and Supreme Court of Canada, as well as in the United States, Japan and Singapore. As his co-counsel in many of them since 1987, I was submitted by him to the same rigorous preparation. Often, he conscripted me in the role of opposing counsel. Responding to his cogent, acidic, relentless advocacy—more oration than argument—guaranteed frontstall preparation (especially considering he frequently and curtly challenged content, structure, style and demeanor of my every oral presentation).

He became one of my invaluable professional mentors. Much his junior at the Bar, I marvelled—with considerable trepidation—at jousting with this icon of Canada's barristers; whose cases I had studied in law school (Dalhousie’s Faculty of Law, 1967).

During a recess—about 3:30 AM—in an 8-hour lecturn rehearsal of an appeal scheduled for later the same day, he recounted to me one of his few court experiences for which preparation proved pointless.

How Q.C. was among trial counsel for Emile Boucher, charged for seditious libel because he publicly distributed some of the 1.575-million copies of a tract, entitled "Quebec's Burning Hate", printed by Jehovah's Witnesses in response to acute oppression they suffered in Quebec during the premiership of Maurice Duplessis.

As he recalled, Boucher's trial was conducted in rural Quebec in November 1947. Inexplicably, all windows in the St-Joseph-de-Beauce courtroom were open on the frigid autumn day when How and co-counsel commenced their jury addresses. Without warning, their voices were overridden by a cacophany of squealing sounds, emitting from a truckload of domestic swine—by chance or design—being discharged onto the adjoining street. If a coincidence, said How, "the timing was precise." But he wasn't convinced the event was fortuitous: "Letting loose a herd of pigs, immediately below open windows of a courtroom in session, did nothing to serve the pork bellies markets." Nonetheless, he was compelled by the court to compete with the porkers for the jury's attention. The pigs, who appeared to linger near the windows for much of the defence jury address, apparently proved, How said, "more attention-fetching and persuasive than me, because the jury later deliberated for about half an hour and convicted my humble farmer client."

How's successful appeal, in 1951, of Boucher's conviction to Supreme Court of Canada was the first of a quintette of largely-successful appeals he argued before that Court; resulting in decisions which impacted enactment of the Canadian Bill of Rights in 1960, and the Charter, in 1982.

As recently as 2003, age 84, he readied, at his office lecturn, for his last case; before Quebec Court of Appeal.

Sometimes vehement in avowing civil rights of Jehovah's Witnesses to preserve, practise and propagate their religious convictions, How, Q.C. was blunt, not infrequently controversial, in deprecating those who sought to denigrate Witness beliefs and deny their promotion. While his religious beliefs were incongruent with mine (as a practising member of United Church of Canada), he was unerringly respectful of my faith during 21 years (1987-2008) he engaged my legal assistance.

W. Glen How, O.C., Q.C., L.S.M., 89, who died 30 December 2008 at his Georgetown, ON home, profoundly advanced Canada's civil liberties. Resolutely and dauntlessly, he challenged intense legal and popular persecution of Jehovah's Witnesses, as their general counsel from 1943 to 2008.

"Throughout the course of his long career," stated American College of Lawyers (08 September 1997) in conferring on him—the only Canadian lawyer recipient—its Courageous Advocacy Award, "[he] demonstrated courage and commitment as a trial lawyer, as an appellate lawyer, and as a human being." (Comparable sentiments had been expressed by MacLean’s magazine in designating him, in 1963, an outstanding Canadian.)

His penchant for law became an adult life-long pre-occupation. He adroitly employed legal precepts as vehicles to overcome public, state and church (particularly, Roman Catholic) attitudes and actions—freighted with derision, distemper, distain, and discrimination—against the Witnesses.

Incontestable is How Q.C.’s impact on recognition, development and growth of Canada's civil liberties, since his admission to the Bar (Law Society of Upper Canada) in September 1943. He was also a member of the Alberta and Quebec Bars.

During 65 years of lawyering—including a private Toronto law practise (1954-1984)—How Q.C. served as counsel for Jehovah's Witnesses—always pro bono—in every Canadian province and in New York (Federal Court of Appeals [2nd Circuit]), New Jersey and Illinois (Supreme Court), Texas, Washington, and Nebraska, and as counsel or consultant counsel in Italy, Trinidad, Japan and Singapore.

Undisputably, however, How, Q.C.—born 25 March 1919 in Montreal—established his legal legacy in Quebec in the 1940s and 1950s.. There and then, during Maurice Duplessis’s premiership (1936-39 and 1944-59) opined former British Columbia Supreme Court Justice Thomas R. Berger, in Fragile Freedoms [:] Human Rights and Dissent in Canada, "Church and State joined in persecuting Jehovah's Witnesses, who carried their struggle for freedom of speech and freedom of religion to the Supreme Court of Canada again and again. …. The fervour of this small Protestant sect had more than a little to do with establishing the intellectual foundations for the [Canadian] Charter [of Rights and Freedoms]." Principal public face of their legal struggle—in confirming, protecting and asserting civil liberties for themselves and, by extension, all Canadians—was W. Glen How.

In the 1940s, How, Q.C. gained enormous litigation experience, primarily in Ontario and Quebec. His clientele, at one time, included about 22 per cent—some 1,600—of all Jehovah's Witnesses then living in Canada); who had been charged—mainly in Quebec—under the Criminal Code or provincial or municipal legislation, for practising their religious faith. Nonetheless, he then managed to author two influential articles for the prestigious Canadian Bar Review.

The first, in 1947 (25 Can. Bar Rev. 573), recommended reforms of Supreme Court of Canada; incorporated by Parliament in 1949 legislation which facilitated How Q.C.’s Supreme Court litigation.

The second, in 1948 (26 Can. Bar Rev. 759), materially contributed, 12 years later, to enactment of The Canadian Bill of Rights.

In 1949, How Q.C. received the first of a series of Supreme Court of Canada judgments, in R. v. Boucher, one ofa quintette of appeals—the others being Saumur, Chaput, Roncarelli, and Lamb—he brought (or assisted to bring) to the Court.

Boucher was convicted of seditious libel (now Criminal Code s. 59(2) ) for publicly distributing "Quebec's Burning hate”, a tract Jehovah's Witnesses published (1,575,000 copies) in response to oppression they were experiencing. A 5-member panel of Supreme Court set aside Boucher's conviction and ordered a new trial (3-2). Boucher successfully applied (9-0) for a re-hearing, which quashed the conviction (5-4). (1949), 93 C.C.C. 371 (S.C.C.); (1950), 96 C.C.C. 48 (S.C.C.); [1951] S.C.R. 265.

The Saumur case began as Damase Daviau’s application to enjoin Quebec from enforcing a municipal by-law which authorized the police chief to license or prohibit circulation of printed matter. Daviau decided not to pursue the application in Supreme Court. A willing replacement—charged more than 100 occasions for his Jehovah's Witness activities—was Laurier Saumur. A complex Supreme Court decision held the by-law could not enjoin Jehovah's Witness distribution activities. [1947] S.C.R. 492; [1953] 2 S.C.R. 299; [1964] S.C.R. 252.

In Chaput, a Jehovah’s Witness was conducting a religious meeting of Witnesses in his Chapeau, Quebec home when Romain and two other Quebec Provincial Police members entered, stopped the meeting, took bibles, hymn books, pamphlets, and a contribution box from the 40 assembled persons, and transported the visiting minister to Ontario. Chaput's resulting civil action against police was successful in Supreme Court; which awarded $2,000 (for what Rand J. characterized an "offensive outrage"). [1955] S.C.R. 834.

Roncarelli was another civil action. The action was commenced by a Montreal restaurant owner, who provided funds to 'bail' numerous arrested Jehovah's Witnesses. His business failed after his liquor license was suspended by the Quebec Liquor Commission, which told him the licence would never be renewed; all on instructions of Premier Duplessis. Supreme Court upheld Roncarelli's trial judgment against Duplessis and added damages for diminished goodwill and future profit loss. [1959] S.C.R. 121 (as consulting solicitor).

Lamb, a third civil action sustained on appeal by Supreme Court, involved Louise Lamb, arrested, while distributing pamphlets in Quebec, by provincial police special officer Benoit who imprisoned her several days, then charged her, although knowing he had no grounds for his police conduct. [1959] S.C.R. 321.

More recently, How Q.C. appeared in Supreme Court

→ as a party, in Young v. Young, [1993] 4 S.C.R. 3, which confirmed, as a general rule, an access parent’s right to introduce a child to the parent’s religious beliefs;

→ in the frequently-cited Charter decision of B.(R.) v. Children’s Aid Society of Metropolitan Toronto, [1995] 1 S.C.R. 315 (role of parents in medical decision making reference their daughter; costs, throughout, awarded his unsuccessful client), and

→ as an intervenor in New Brunswick (Minister of Health and Community of Services) v. G.(J.), [1999] 3 S.C.R. 46, ‘supporting’ a mother who successfully contended for the right of parents of state-apprehended child to state-funded legal services).

Perhaps his cardinal triumph in provincial appellate courts is Malette v. Shulman (1990), 72 O.R. (2d) 417 (Ont. C.A.), which confirmed an adult’s right to respect for his or her advance health care treatment decisions.

His last court appearance was in 2003 (231 D.L.R. (4th) 706 (Que. C.A.)

How Q.C. is survived by his second wife, lawyer Linda J. How, J.D. (Indiana University), to whom he was married in 1989 (his first wife of 33 years, Englishwoman Margaret Biegel, died in 1987). He is survived also by brother John, and stepson Paul Biegel.

A memorial service for W. Glen How, attended by more than 1,400 mourners, was conducted 10 January 2009 at the Assembly Hall in Norval, Halton Hills, ON; ten minutes' drive from his law office—and his cherished Court rehearsal lecturn—in Georgetown.

This law firm conveys heartfelt sympathy to How Q.C.’s widow, Linda J. How, J.D.; Canadian lawyers Shane H. Brady, LL. B, David M. Gnam CGA, L.L. B., and Jason D.A. Wise, L.L. B.; international counsel John Burns L.L. B. and Andre Carbonneau L.L. B. (presently in Kazakhstan); and the remarkably competent professional support staff at W. Glen How & Associates LLP, Georgetown; all of whom worked closely with W. Glen How.

David C. Day, Q.C.

Lewis, Day,

St. John’s, NL

Authors

▓

Revised edition of Matrimonial Property Law In

Canada [Newfoundland and Labrador],

current to 08 January 2008, published February 2008 by Carswell, Toronto

and is available from the publisher in hardcopy, or on the publisher’s website:

Carswell LawSource.

Ethics

▓“"Guidelines for Practicing Ethically with New Information Technologies”

published August 2008 by Canadian Bar Association as Information to

Supplement the Code Of Professional Conduct of the Association

LEWIS, DAY LAW